What sensors are inside the IMU and how do they work?

Inertial measurement units typically consist of three different types of sensors. The first type of sensor is an accelerometer, which measures acceleration, or the rate at which an object accelerates or decelerates. While there are many different sensor technologies for accelerometers, by far the most common for wearable applications is MEMS (microelectromechanical systems). MEMS are sensor systems composed of electrical and mechanical components, typically etched from micron-sized silicon.

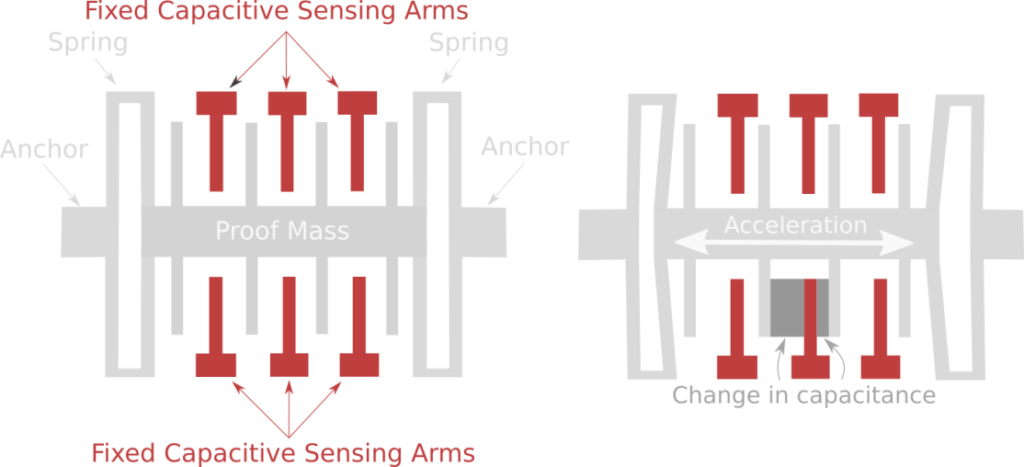

Whenever the MEMS accelerometer experiences acceleration, the proof mass also experiences that acceleration. An etched spring set resists this acceleration. Using Hooke’s law (spring force is proportional to the distance the spring is compressed) and Newton’s second law (force is proportional to acceleration), check that the distance a mass moves is proportional to the acceleration it experiences (see figure below). This movement is sensed using the electrical properties of capacitance, which is related to the distance between two conductors. A set of electronics is then able to measure the change in capacitance, calibrate the signal, and further process it to give acceleration.

The second type of sensor in an Inertial measurement unitis a gyroscope, which measures angular velocity, or the speed and direction of an object’s rotation or spin. Gyroscopes also typically use MEMS technology, although they are more complex than MEMS accelerometers. The main physical phenomenon used in gyroscopes is the Coriolis effect, which describes the forces involved when an object moves in a rotating reference frame.

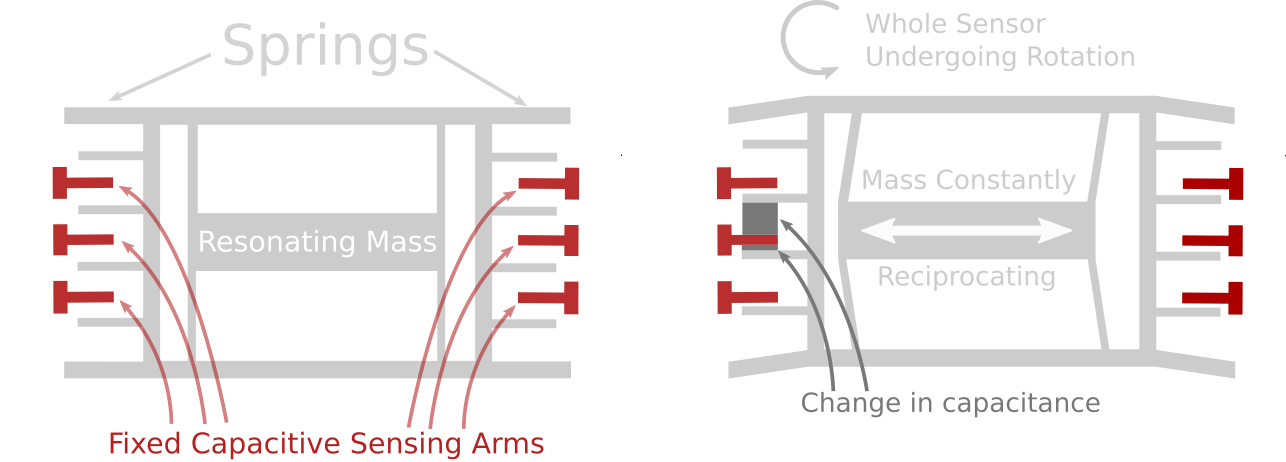

MEMS gyroscopes have masses that reciprocate at a constant frequency. During the rotation of the gyroscope, due to the Coriolis effect, the mass will induce a force perpendicular to the direction of the reciprocating motion. This force is counteracted by an etched spring and sensed by a capacitive sensing arm such as an accelerometer. Signal processing electronics then process the change in capacitance relative to the reciprocating motion of the resonant mass (see figure below).

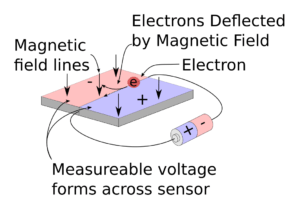

The final sensor commonly found in Inertial measurement units is a magnetometer, which measures the strength of a magnetic field and acts somewhat like a digital compass. Most magnetometers use the Hall effect to measure magnetic field strength. The basic premise of a magnetometer is that electrons moving in a conductor are deflected by the magnetic field to which the conductor is exposed. When charges pass through a conducting plate in a magnetic field, the magnetic field deflects the electrons to one side of the conducting plate. As more negative charge builds up on one side of the plate and more positive charge builds up on the other side of the plate, there is a measurable voltage between the two sides of the plate that is proportional to the strength of the magnetic field.

.jpg)